It should come as no surprise that I have hundreds of cookbooks, most of which are baking books. I own a previously used copy of Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Better Homes and Gardens New Cookbook, and of course, The Joy of Cooking. I have countless antique cookbooks and community cookbooks. If a magazine has an interesting recipe, I can’t bear to throw it away.

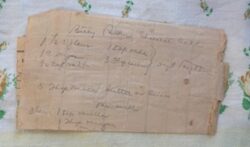

But the most cherished recipes I own are the handwritten ones from friends and family members, handwritten on an index card, a recipe card, a scrap of paper, or the back of an old envelope in their handwriting. I usually had requested them after a special gathering. Was the recipe that good, or was the occasion that memorable? Was it because that recipe came from a friend or a family member who is no longer with us?

Once upon a time, recipes were referred to as “receipts.” I uncovered this interesting fact while conducting research for “Sentimental Sweets.” At first, I thought it was an antique spelling of some sort, but further digging into the subject revealed that, no, they really were calling them receipts. My first question, of course, was “Why?” and then my second question was, “When and why did this change?”

Being the “word nerd” that I consider myself to be, the first thing I did was to look up the definition for the word “recipe”:

Recipe: noun

- A set of instructions for making or preparing something, especially a food dish:

A recipe for a cake.

- A medical prescription.

- A method to attain a desired end:

A recipe for success.

https://www.dictionary.com/browse/recipe

Then I looked up the word “receipt”:

A writing acknowledging the receiving of goods or money (noun)

To give a receipt for or acknowledge the receipt of (verb)

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/receipt

I looked up several other versions of the definition of “receipt,” and none mentioned anything to do with food.

Overly fascinated with this idea, I continued to dig. The first real clue I found was in the book, “The American Kitchen,” where it was called a receipt book:

“A housekeeper’s handwritten collection of culinary and medicinal recipes. During the early Victorian period the mistress of the house would copy a recipe from her book and give the “receipt” to the cook.

There is a problem with this definition.

According to Janet Theophano in Eat My Words, women’s literacy levels varied widely in England and America until the nineteenth century. Chances are that the cook didn’t know how to read, so handing her a written recipe to cook from may not have gotten her very far. Since I was not satisfied that this was the answer, I went back to Miriam Webster, where a further discussion of the etymology showed the link from the Latin origin:

“Both receipt and recipe derive from recipere, the Latin verb meaning to receive or take.”

Theophano gave me the first real piece of the puzzle. She states, “From at least the 17th century, women have exchanged and shared recipes (also called receipts) until the late 19th century…”

Now, it was starting to make sense.

The Receipt Book

Early housekeepers did not have the luxury of the many cookbooks available in modern times. Writing paper itself was expensive, let alone a bound book. To solve the problem of lack of access to paper, women often repurposed books discarded from other uses, such as a business account ledger or, in the case of Sentimental Sweets, an old five-year diary.

Young girls would begin collecting recipes in preparation for marriage. It was not unusual for these recipes to be written on scraps of paper. She would then recopy the recipe into her book. She would have received most recipes from friends, family members, and various acquaintances. Perhaps this is why they were initially called “receipt books” instead of recipe books. Theophano points out, “Just as often, even when rewritten, scraps were preserved. Perhaps because the original might have been written in the donor’s hand, it was kept as a memento, a visible token of the gift, a commemoration of the relationship.” I often find loose recipes tucked into the pages of the antique cookbooks I collect. These are as valuable to me, or even more than the actual cookbook itself.

Recipe Exchanging

Women have been exchanging recipes for centuries. Susan Leonardi discusses the significance of recipe exchange in her article “Recipes for Reading: Summer Pasta, Lobster a la Riseholme, and Key Lime Pie “(1989). She points out that there is far more to a recipe than “simply a list of ingredients and the directions for combining them.” Every recipe has a story: a special occasion that it was prepared for, a beloved friend’s favorite dish, or a comfort food from childhood.

For centuries, recipe exchange has allowed women to cross the social barriers of class, race, and generation. Recipe exchange could occur between mother and daughter, neighbor to neighbor, or mother-in-law to new bride. Those participating in the exchange may have barely known one another. It could be between “lawyers and their secretaries,” servants and the lady of the house, or, as Theophano mentions, “a reason to initiate a correspondence” in writing to request a copy of a recipe once enjoyed together.

Recipe Withholding

To share a recipe is an act of trust between women. Recipes can be the actual token in a gift relationship. “When we exchange recipes, we are exchanging mementos of friendship” (Theophano, 2016).

My research on the subject of recipe exchange led me to an online baking forum of which I was unaware. One topic of discussion involved recipe withholding. The question was, if you are going to a potluck and you are not going to divulge the recipe, should you still bring the dish?

I never realized what a hotly debated topic this could be.

Quite a few members posted their evasions to this request, such as, “Well, there’s not really a recipe; it’s a little of this and a dash of that.” Or there’s the ever-popular, “I still give them the recipe, but leave out a couple of ingredients.” Ouch.

One member in favor of recipe sharing replied that one of the saddest things is when someone takes a recipe to the grave. The survivors have only the memory of the dish but no way of replicating the dish they crave (BrownieBaker, https://forums.egullet.org/topic/33577-recipe-etiquette/ December 18, 2003).

(Oh, how I wish I had Aunt Jewel Ward’s chocolate cake recipe. And her iced brownie recipe, too).

Leonardi gives some examples of recipe withholding in her 1989 article, complete with some very humorous literary examples. The rivalry between Elizabeth and Lucia for Lucia’s recipe for Lobster a la Riseholme in the 1931 comic novel Mapp and Lucia by E.F. Benson takes recipe withholding to Biblical significance (which, by the way, was made into a series in 2014 and is available on Prime. I am currently scheduling time to binge watch it).

Why do some of us withhold or modify a recipe so that it can’t be exactly reproduced? Some cooks feel their recipes should be a closely guarded secret and will not share a recipe. It’s as if someone knows your secret recipe; well, there goes your claim to fame. This is especially true of requests for family recipes handed down from generation to generation.

For those of us worried about divulging ancient family secrets, Thomas Keller gives a great perspective in The Omnivorous Mind:

“You’re not going to be able to duplicate the dish that I made. You may create something that in composition resembles what I made, but more important—and this is my greatest hope—you’re going to have deep respect and feelings for. And you know what? It’s going to be more satisfying than anything I could ever make for you.”

Janet Theopoulos puts her spin on this idea: “The recipe is a copy of its original, a dish that would not be duplicated exactly even in its own time, and each subsequent attempt to reconstruct it, a copy of the copy.”

A legend in my family goes like this:” No one could exactly reproduce Aunt Jewel’s chocolate cake, even if she stood right next to you when you baked it.” (I still wish I had that recipe).

When did we actually stop using the word receipt?

Despite my research, I have not been able to pinpoint exactly when or why we stopped using the word receipt to mean a recipe. The closest idea I could find came from a statement made by Emily Post in 1922:

” Receipt has a more distinguished ancestry, but since recipe is used by all modern writers on cooking, only the immutable (unchanging) insist on receipt.” Post goes on to describe the

term receipt as a word of fashionable descent, while recipe, she said, had more of a commercial air.

Every Recipe Has a Story

All of this may be obvious to everyone but myself. Before Sentimental Sweets, I thought of recipes as just a list of instructions for cooking. Researching for this book has opened up a whole new world that I did not know existed. I had no idea people bought and read cookbooks…just to read them. I had never thought much about recipe construction or the all-important head note, which is actually the backstory, the real heart of the recipe. I was always guilty of “cutting to the chase…” this looks good; how do you make it? Not where this recipe came from, how old it was, or the stories of the events where it was served.

A recipe is so much more than just instructions on baking a cake or making a pasta dish. A recipe is a connection: between friends, between family, and between generations.

I was beginning to think I would never find a definitive reason that recipes were once called receipts. Finally, I found the “magic” definition that explained everything. It was interesting that I found it on an investing website:

Receipt (noun): a written acknowledgment that something of value has been transferred from one party to another.

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/receipt.asp

Write down those recipes that are “a little of this,” “a dash of that.” Make a note of the special occasions where it was served and the people who were there to share it. Pass that recipe on to friends and family.

Recipes are so valuable they were once called receipts.

Here’s a short list of some vintage receipt books:

Title Author Year Published Of Note

| The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy: To Which Are Added, The Complete Family Piece, and The Receipts of The Famous Mrs. Glasse | Hannah Glasse | 1747 | One of the most famous British cookbooks of its time, it helped popularize “receipt” as the term for recipes in England. |

| The New Family Receipt Book | Richard Briggs | 1798 | This cookbook contains a large number of recipes for both food and household management. |

| The New England Receipt Book | Mrs. S. T. Rorer | 1860 | A cookbook focused on the regional cuisine of New England, with many “receipts” for traditional dishes that are still popular in the region today. |

| The Household Receipt Book | Sarah Josepha Hale | 1857 | Sarah Hale, best known for writing “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” also authored this practical guide for women, which includes recipes (or “receipts”) along with advice for managing a household |

| The Southern Receipt Book | Marion Cabell Tyree | 1871 | This cookbook focuses on the Southern U.S., featuring a collection of regional recipes and household tips. It’s a reflection of the culinary traditions in the South during the post-Civil War period. |

| The Cook’s Own Receipt Book | Mrs. F.L. (Frances L.) Gould | 1867 | A mid-19th century American cookbook that offered recipes for a variety of meals and emphasized home-based cooking for families. |

| The American Woman’s Receipt Book” | Mrs. H. H. (Hannah) Knapp | 1864 | A cookbook designed for the home cook, filled with practical “receipts” for American households, with a strong focus on simplicity and economy |

| The Complete Cook’s Receipt Book” | Charles C. H. Gould | 1872 | This cookbook is a thorough guide to American cooking, offering a variety of recipes, including many from the New England and Southern traditions. |

Both of these are recipes I found in a 1942 edition of “Women’s Home Companion Cook Book.”

References:

Allen, J. S. (2012). The Omnivorous Mind. Harvard University Press.

Leonardi, S. J. (1989). Recipes for Reading: Summer Pasta, Lobster a la Riseholme, and Key Lime Pie. PMLA, 104(3), 340. https://doi.org/10.2307/462443

Plante, Ellen M. (1995) The American Kitchen, 1700 to the Present. Facts on File, New York.

Theophano, J. (2016). Eat My Words. St. Martin’s Griffin.